An introduction to Clarks Mill

Imagine a flour mill, one of this country’s earliest, built of Oamaru stone quarried from a nearby escarpment and rising imposingly above the North Otago landscape. Now picture walking inside, where someone has just flicked the switch that sets in motion four storey’s worth of rare vintage milling machinery. In an instant, Clarks Mill is transformed from a static heritage landmark into something like a living organism, all spiralling shafts, spinning belts and the whirr of pulleys. It’s incredible.

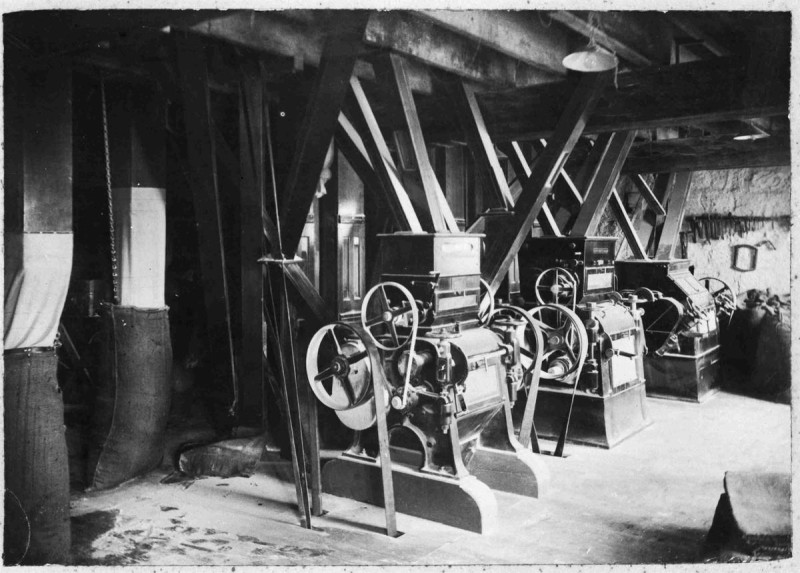

Clarks Mill machinery, Collection of the Waitaki Archive. Id 101283

"Clarks Threshing Mill", c.1910. Collection of the Waitaki Archive. Id 104055

You won’t witness Aotearoa New Zealand’s only surviving orginal water-powered mill in action without some forethought, however. For safety reasons the mill can’t operate without a volunteer on each floor, which means visitors should book ahead for a group tour. Alternatively, keep an eye out for their operating day, when the mill is running and the miller’s house is open to visitors.

Even when not in action, Clarks Mill is a fascinating example of colonial engineering smarts, and evidence of the central role played by wheat growing and flour milling in the early North Otago economy. Opened in 1867 for the New Zealand and Australia Land Company, it was originally equipped with grinding stones powered by a water wheel. The awkward location – for obscure reasons the mill was sited in a bend of the Kakanui River rather than beside it – required the construction of a long water race and tunnelling. In the 1890s, the mill was upgraded to roller machinery powered by turbines.

The family that gave the mill its name took over ownership in 1901. The four Clark brothers were an enterprising bunch – some of their other ventures included quarrying and exporting Oamaru stone, contract harvesting and a transport operation – and they progressively modernised the mill over the following decades, incorporating the latest tech with the original 1870s machinery, which was eventually powered by electricity. Perhaps it looked a little inelegant, but the Clarks Mill plant ran like a dream, operating 24 hours a day with only one miller required per shift to keep an eye on things.

And it kept running – asole survivor from another economic era. It wasn’t until the mid ’70s, half a century after the demise of other small milling operations, that Clarks Mill finally ceased operation. Bought by Historic Places Trust (now Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga) it went through a major restoration in the 1980s. More recently, a posse of committed volunteers that has included two descendants of the Clark brothers has reanimated the machinery. This “League of Extraordinary Gentlemen”, as one of our stuff dubs them, run the guided tours and are enthusiastic mines of information.

If you’re curious about our industrial history or an engineering buff, you’ll find the mill’s inner workings enthralling. If the mill is not your thing, the Clarks Mill complex also includes a miller’s house and garden as well as ‘Smokey Joe’s’. The latter, a stone cottage neighbouring the house, was set up as a night club by one of the Clarks after he returned from WWII. With its walls painted in exotic scenes, a busy bar in one corner and a ubiquitous cigarette haze, Smokey Joe’s became a North Otago legend. Both cottage and house are only open on live operating days. However, the colourful garden, which has been recreated based on Clark family photos from the 1940s using bright dahlias, asters and heritage roses, can be viewed any time.

When you’re ready to explore, drive on to Kakanui Beach for a surf or perhaps a feed of fish and chips from one of the locals. Keep an eye out for whitebaiters at the river mouth and Hector’s Dolphins playing in the surf.

Photo: Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga